Tracing My Swedish Ancestry

Introduction

My wife Annette and I decided to vacation in Sweden in the summer of 2012. I had only been to Malmö for half a day back in 2004, as an excuse to take the Öresund Bridge. I had always wanted to visit Stockholm, and Annette was excited to try a smörgåsbord.

I knew that my father’s relatives had come to America from Sweden around the turn of the century. My dad confirmed this for me… His father, Oliver Oberg, came to the USA as a young boy with his family. Oliver’s father was Peter Oberg, and Peter brought the family from an area of Sweden called Jämtland. That was about all I knew.

I decided to do some ancestry research and try to find the town or village where the Oberg’s came from. My big hope was to travel there and take a picture next to a city sign or landmark. I did not have any plans beyond that.

The Obergs in America (mostly just in Maine)

I started my research using ancestry.com, and I have to say, their tools and databases were super useful. They have searchable US census data online from 1940 and earlier. Ancestry.com also gave me access to extensive Swedish parish records. There are online photos of most of the Swedish family records, which were originally hand-written yearly by local priests.

I started with my mom (Ruth Weidman) and dad (Stuart William Oberg) and my dad’s parents (Oliver Oberg and Vivian Hamlin), and my great-grandfather (Peter Oberg). Ancestry.com’s tools made it easy to track down census data for everyone, as well as other records like marriage and death certificates. You can see my current Oberg family tree here.

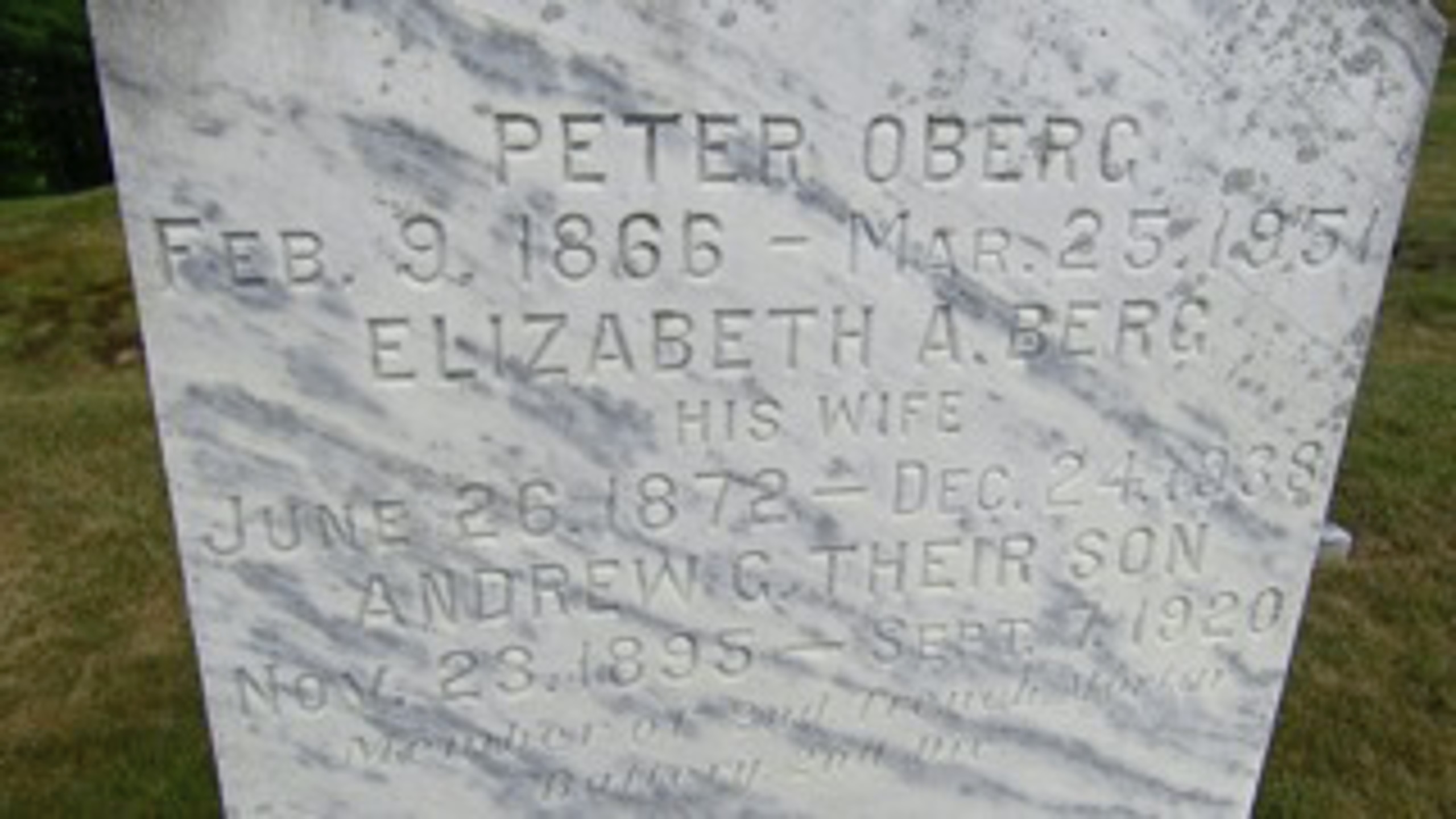

Pretty early on, I found a picture of Peter (and his wife Elisabeth) Oberg’s grave site at Brownville Village Cemetery in Brownville, Maine:

The dates on this gravestone are super valuable when doing this ancestry research. We’re pretty sure that the family knew these dates well, and thus that they are correct. You can then uses these dates to confirm other records that may or may not refer to these people. Once I had these dates in hand, it was fairly straightforward to find indexes US census records for Peter Oberg’s family going back to 1910.

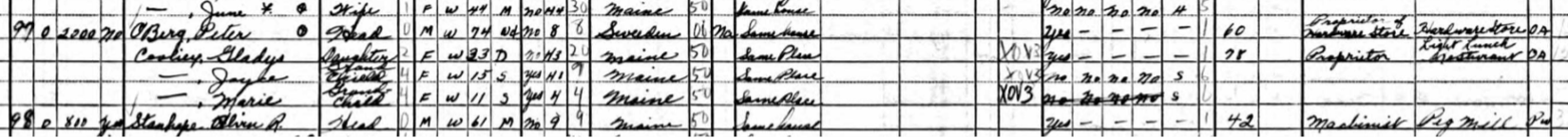

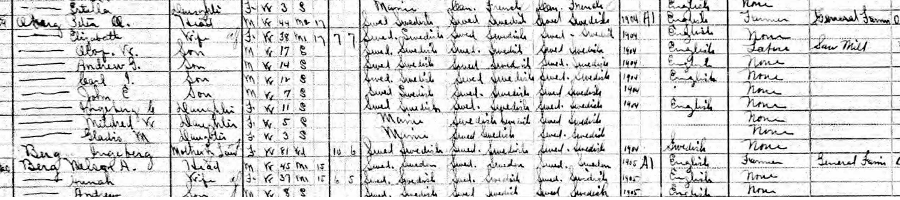

We’ll start with the 1940 census and go back in time.

We can see here Peter’s wife is not living with him, which makes sense, since the gravestone says she died in 1938. Also notice that Peter is living with his daughter Gladys and her two children, all of whom have taken another family name. We can see here a slight transcription error on the part of the census taker; they have written OBerg, as if the name is Irish.

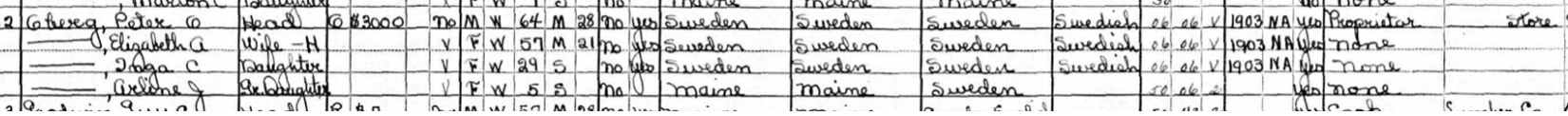

Travelling to 1930, we see this:

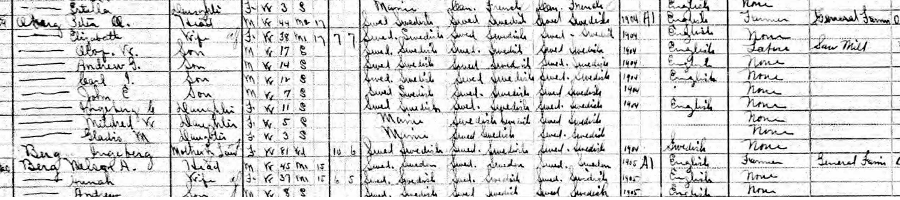

Peter and Elisabeth are living with their daughter Inga, and her child. Note that Peter’s and Elisabeth’s ages match what they would have been in 1930, according to their gravestone. Another error has crept into the record… the “1903“s written refer to each person’s immigration year. We know from several other records that the family came to America in 1904. Either the family or the census taker made a mistake with these dates.

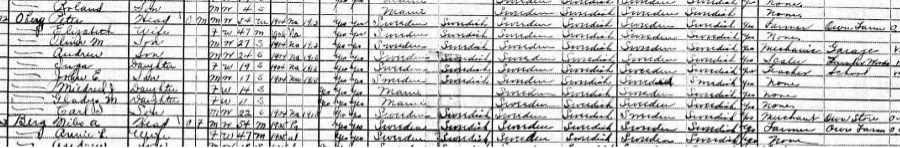

This is most of Peter and Elisabeth Oberg’s family as we know it. Oliver is the eldest son; he’s 27 and working as a mechanic. Note that Mildred and Gladys are listed as being born in Maine, which jibes with the “1904” next to the other family members… that column is their immigration year. Again, all the ages match with what we know.

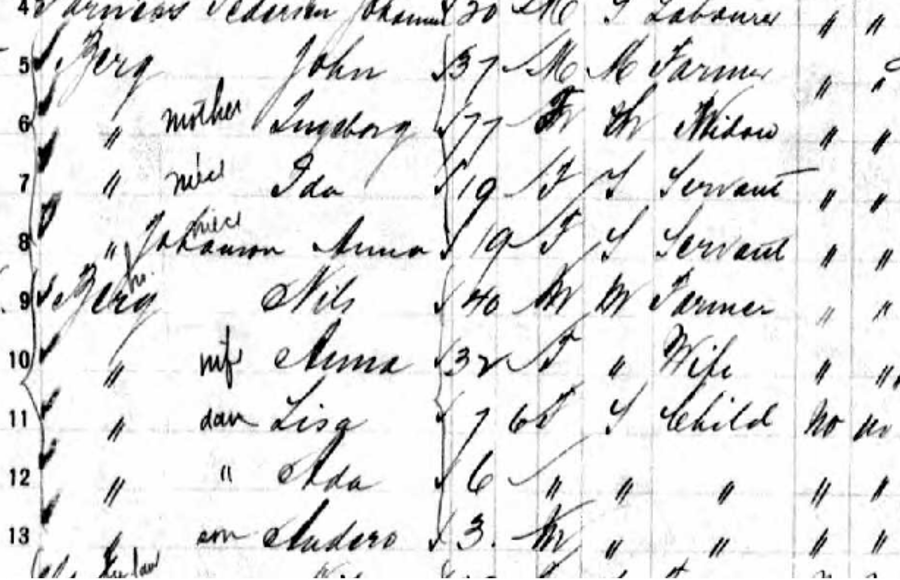

Now we go back to the earliest record of the Oberg family in America, the 1910 census:

First off, it appears that Oliver’s name was originally Olof! This was a crucial bit of info for tracking down his birth records in Sweden. Secondly, it appears that the family lived with Peter’s mother-in-law (i.e. Elisabeth’s mother) Ingeborg. Recall that Elisabeth’s gravestone listed her last name as Berg, not Oberg. I don’t know why she did not take Peter’s last name, but I was glad she didn’t. Her unique last name was very useful when looking at Swedish records.

One more thing in these 1910/1920 censuses (censi?) sort of jumped out at me. Notice that the family listed after the Obergs are the Bergs. I would guess that many of these censuses were taken by workers walking from house to house, so people listed next to each other were likely to be neighbors. Elisabeth’s family name was Berg, her mother lived with her, and the neighbor’s name was also Berg. In addition, the neighbors immigrated one year after the Obergs did. From all this, I believe that Elisabeth Berg was Nils Berg’s brother. My only corroborating evidence is this 1905 New York passenger list that includes Nils Berg, his brother John, and their mother Ingeborg.

Crossing the Atlantic

At this point in my searching, the various immigration records (Ellis Island, et al) has not turned up any info on exactly where Peter and Elisabeth Oberg’s family arrived in the US. I knew it was in 1904, from the census records above, and from Swedish records I’ll talk about later. Much later in the process, I was able to find travel documents for the family.

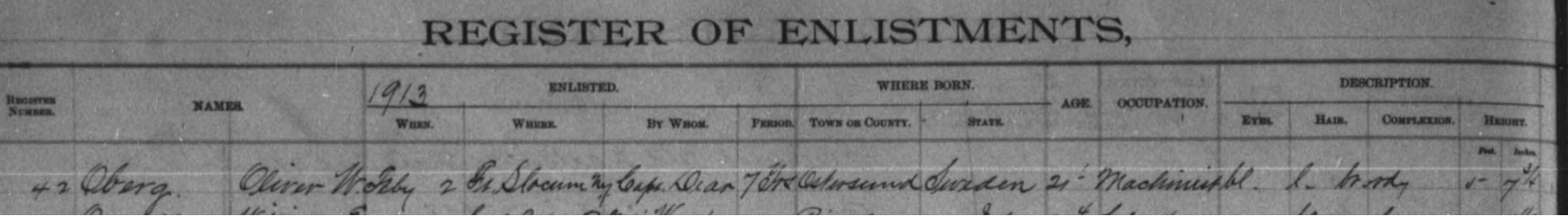

I knew that Oliver Oberg served in the US Army in WWI. Ancestry.com tracked down his enlistment record, where he claims that he was born in Ostersund, Sweden (which is part of Jämtland):

The Swedish household records in the 1800’s are pretty amazing. Priests would visit local homes every year, ensure that everyone’s name was written down in the “household book”, and then keep track of who could read that year. I also believe they gave some sort of regular liturgy test. In addition, they had separate books for births and marriages. All these records have been photographed and are online. There are only two problems: 1) they are in, er, Swedish, and 2) they are hand written in cursive. This means that you can spend a lot of time just trying to read the darn things.

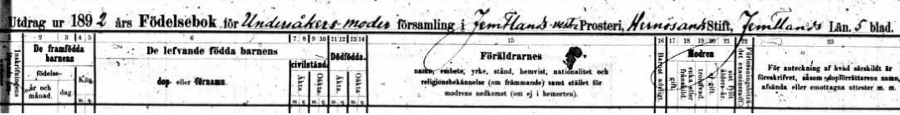

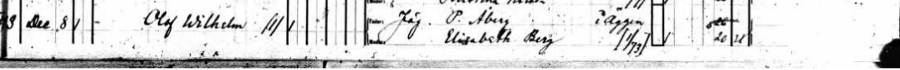

At this point, ancestry.com listed a birth record that might have applied to Olof Oberg. It had a low probability of matching, but I looked at it anyway:

(snip)

There’s some weird stuff here, but it seems promising. First off, it’s from Jämtland. Secondly, the mother’s name is Elisabeth Berg, and she is listed as being 20 years old in the year 1892, which agrees with our Elisabeth Berg’s gravestone. The township is listed as “Undersåker”, which is about 60 miles west of Ostersund. So this might be a record of Olof Oberg’s birth. But the father is listed as P Åberg, which may or may not mean Peter Oberg. Could the Oberg family have really been Åbergs back in Sweden?

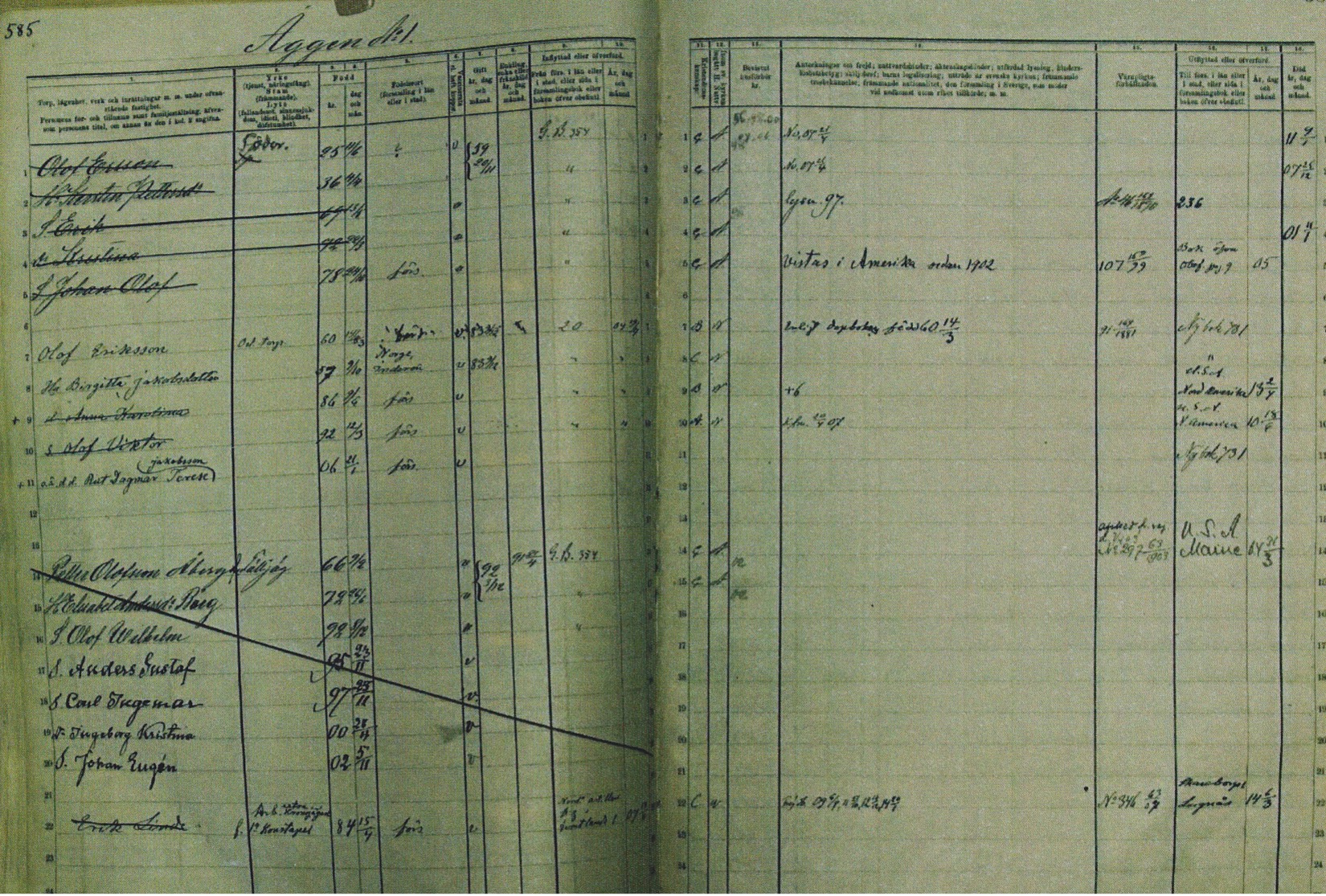

The answer turns out to be yes. I searched the Undersåker household records for families named Åberg, and found this key document:

This is really amazing. In the bottom half, you can see the Åberg family, starting with “Petter Olofsson Åberg”, followed by his wife Elisabeth Andersson Berg and son Olof Wilhelm. The next listings, however, are the key to our cross-Atlantic puzzle. After Olof, the children listed are Anders, Carl, Ingeborg, and Johan. These match up one for one with the Oberg children listed in the 1910 census:

Yes, the names are Americanized… Anders becomes Andrew and Johan becomes John. But the middle initials and ages match up as well. This convinced me that the Oberg family of Brownville, Maine is the same family as the Åberg family of Undersåker, Jämtland.

There are some other tidbits in this Swedish record as well. The family is crossed out because they moved away. In the far right column you can see that they are listed as moving to Maine USA on 31 March, 1904. The column to the right of the names lists exact birthdates. These match up with the gravestone of Peter and Elisabeth and their son Andrew. From all this, it’s clear to me that this Åberg family are my direct relatives.

The Plot Thickens

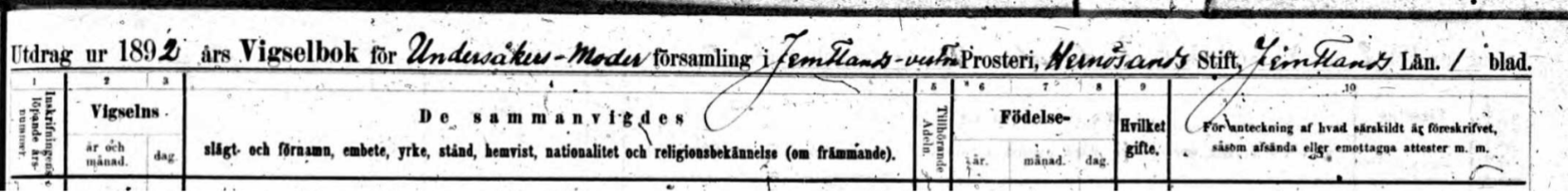

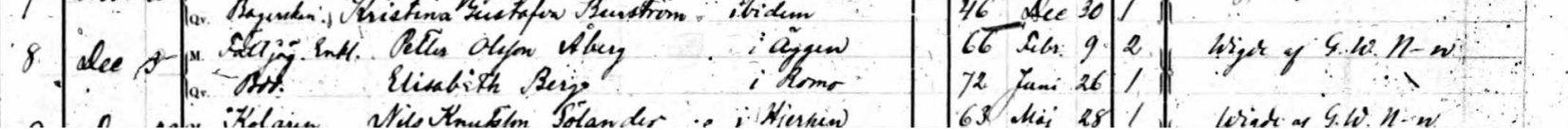

Another datum in the Swedish household record is a date to the right of Peter and Elisabeth’s birthdays. I decoded it as 3 Dec 1892. I guessed that this was the date that they married, and I went searching through the Swedish marriage records for Undersåker. I quickly found this listing:

(snip)

This is the 1892 marriage book for Undersåker. Peter Olafsson Åberg married Elisabeth Berg on 3 Dec. This also lists were they were from… Petter was from Äggen, and Elisabeth was from Romo. In fact, if we go back to the household record, we can see that same name… Äggen:

It’s right there at the top… Äggen is the village or farm or property name where Petter was from, and where the Åbergs lived after they married. Sadly, I was not able to find Äggen in Google maps. But knowing the property name allowed me to search in some other household records where I found this earlier listing for the Åberg family:

This is another super interesting record. We see Petter and Elisabeth and Olof with the birthdates we would expect. We also see Petter listed (and crossed out) in the upper half with the same birthday. This is because the upper listing is the family that Petter grew up in. Petter’s middle name is Olofsson, which agrees with being the son of Olof Ersson, who is listed at the top of the page. Some other research confirmed that Petter’s father (and thus my great-great-grandfather) was indeed Olof Ersson. This implies another fascinating fact.

The Åberg family name started with Petter. It was given to him at birth, and was part of the nationwide shift away from the strict patronymic naming system that had been in place. We also know that Olof and his wife Kerstin earlier had a son Petter who died at 8 weeks. It’s possible that the second Petter born to Olof and Kerstin was given the Åberg name to distinguish him from his namesake little brother. Åberg literally means “mountain stream”… å (pronounced ooeh) is a “stream” and berg (pronounced berry) is “mountain”.

The Åberg family listing in this record also contains a strange crossed out entry. It turns out that Petter was married to a woman named Oline Martina Hansdotter on 7 Dec 1890. On 21 Apr 1891, she died of tuberculosis. Twenty months later, Petter married Elisabeth.

Speaking of which, as I looked over all these dates, I noticed that Petter and Elizabeth were married on 3 Dec 1892. Their firstborn son, Olof Wilhelm, was born on 8 Dec 1892. I don’t know if a shotgun was involved, but it appears that my grandfather was 5 days away from being illegitimate.

Travelling to the Motherland

I was pretty happy with the results so far. I know that my (almost illegitimate) grandfather grew up in an area called Äggen, and that the entire family emigrated to Maine in 1904. The big mystery for me was Äggen. Where was it? Does it still exist? My goal for the trip was still the same… I wanted to get a picture next to a sign for Äggen.

I knew that Äggen was part of Undersåker in Jämtland, and that Undersåker was about 60 miles west of the capital Östersund. Östersund has the area’s “land archive” office which contains all the physical records that I was searching online. Annette and I decided to spend a few days in Östersund to see if we could locate Äggen with the help of locals there. Even if we couldn’t find Äggen, our plan was to drive to Undersåker and at least get a few pictures of the scenery.

We arrived in Östersund on 8 Aug 2012 and went immediately to the land archive office. Here I am outside of it:

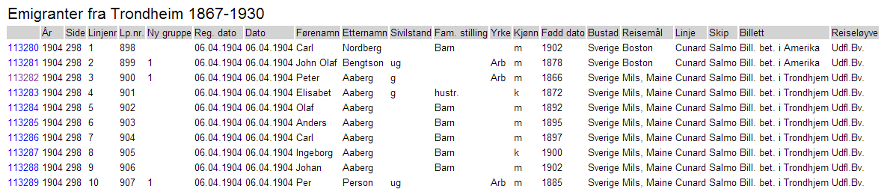

The archivist was super helpful, and she quickly got me hooked up with some maps and web pages for tracking down where Äggen was. They also had a more diverse set of emmigration records. I learned that most emmigrants from Jämtland departed from Trondheim in Norway, and that the Norwegians used “Aa” when they encountered the Swedish letter “Å”. From these facts, I was able to find an online passenger listing for the Åberg’s 1904 trip from Trondheim:

(snip)

You can see that they were listed as going to “Mils, Maine”, which probably is a mistransscription of “Milo, Maine”. Also, they left on the Cunard ship “Salmo”.

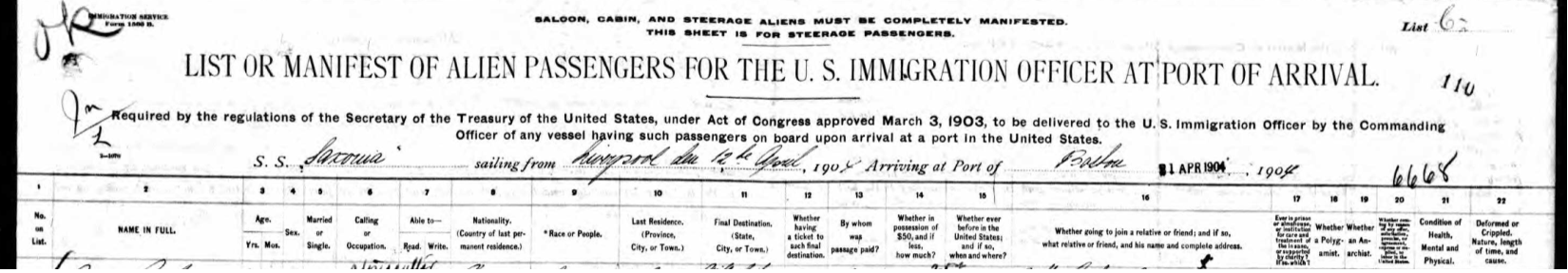

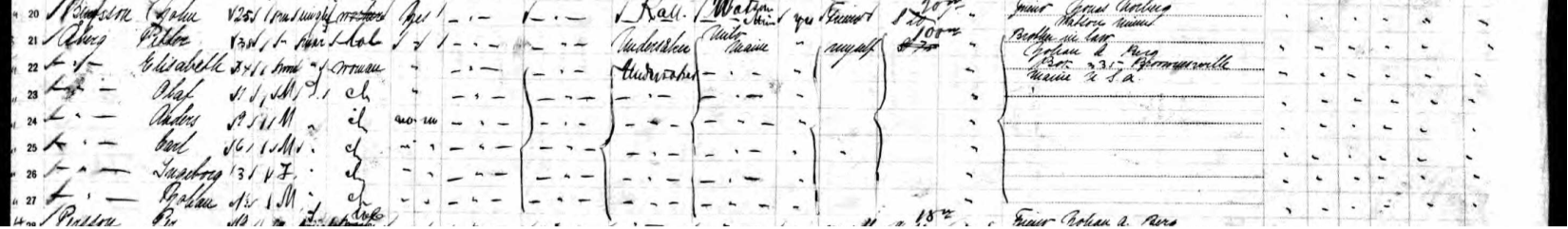

I was eventually able to also find the passenger list for the family’s arrival in Boston:

(snip)

“My Homeland Undersåker”

While I was digging through that stuff, Annette was wandering around the offices, which had the feel of a small library. The archivist brought Annette a book which she said was sort of an informal history of Undersåker. Here’s the title page:

The title is (roughly) “My Homeland Undersåker”, and it was written in 1954. The book is a written record of a bunch of stories that had been part of the area’s oral history. I thought of it as sort of a real-life “Lake Woebegon Days”.

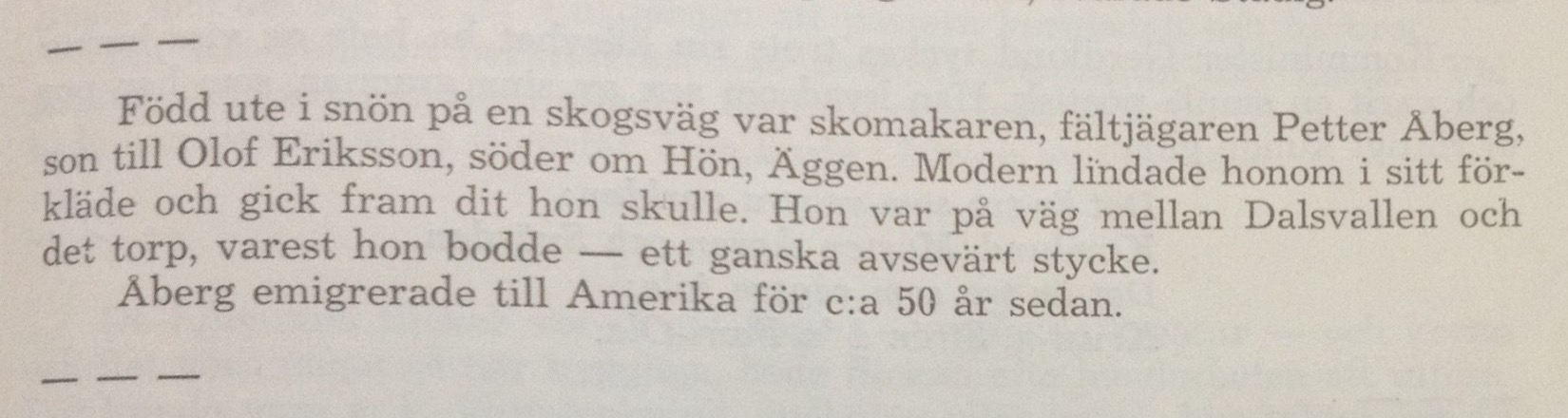

While I was immersed in the maps/computers, Annette had the good sense to look up Åberg in the book’s index. To her delight and surprise, there was an entry for Petter Åberg. It was one small paragraph in the back of the book:

We asked the archivist to help translate the passage, and she had a bit of trouble. With some help from Google translate, we got a good translation:

Born in the snow on a forest road was cobbler and soldier Petter Åberg, son of Olof Ericsson, from south of Hön, Äggen. His mother wrapped him in her apron and went on her way. She was on the road between Dalsvallen and the cottage where she lived - quite a considerable distance.

Åberg emigrated to America about 50 years ago

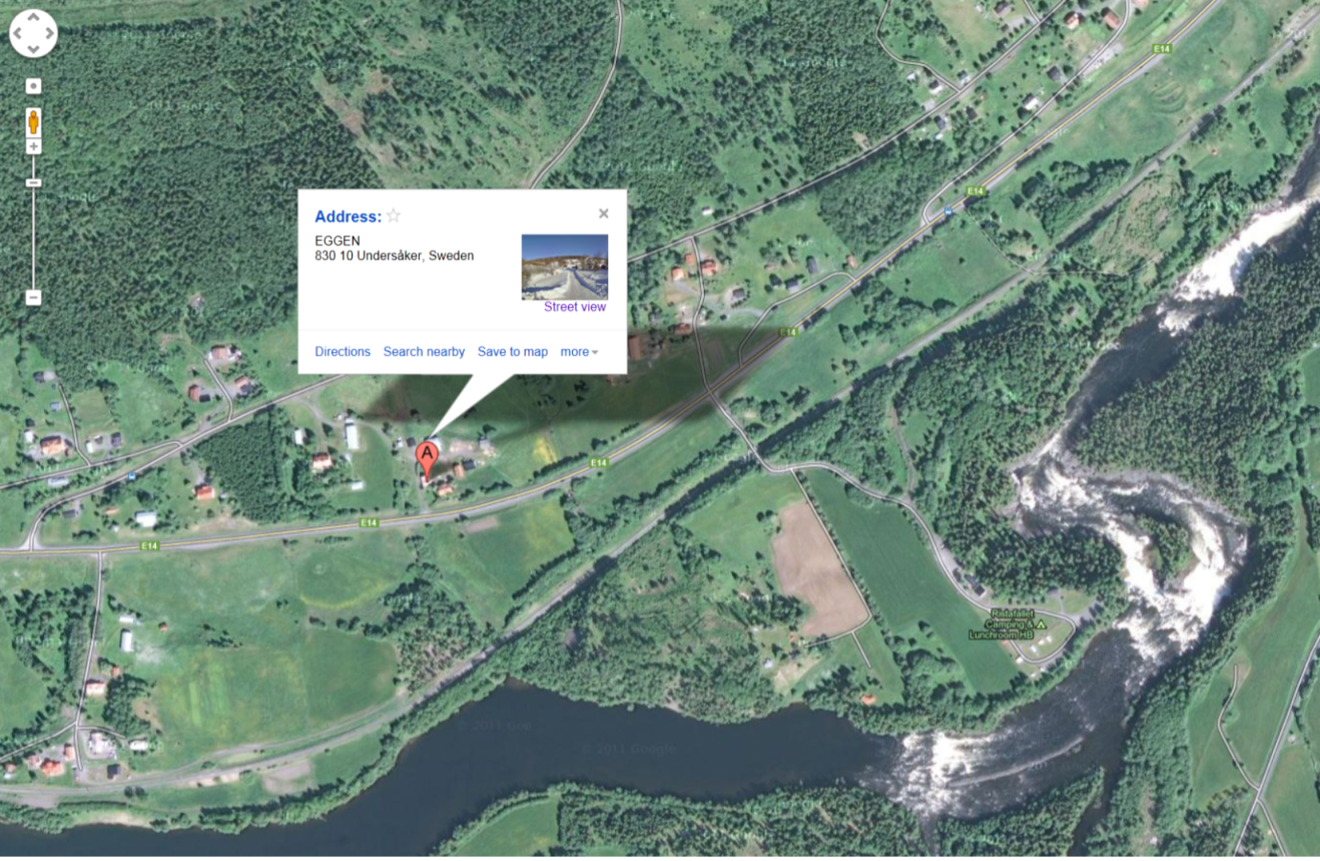

HOLY CRAP! This is certainly a story about my great-grandfather Peter… the emigration date matches, and it mentions Äggen. It turns out that his father Olof’s name is slightly incorrect (listed as Ericksson when it’s really Ersson), but the added detail of Dalsvallen helped us pinpoint where Äggen is. Modern maps list Äggen as Eggen (it literally means “eggs”), and Google maps had an address that matched:

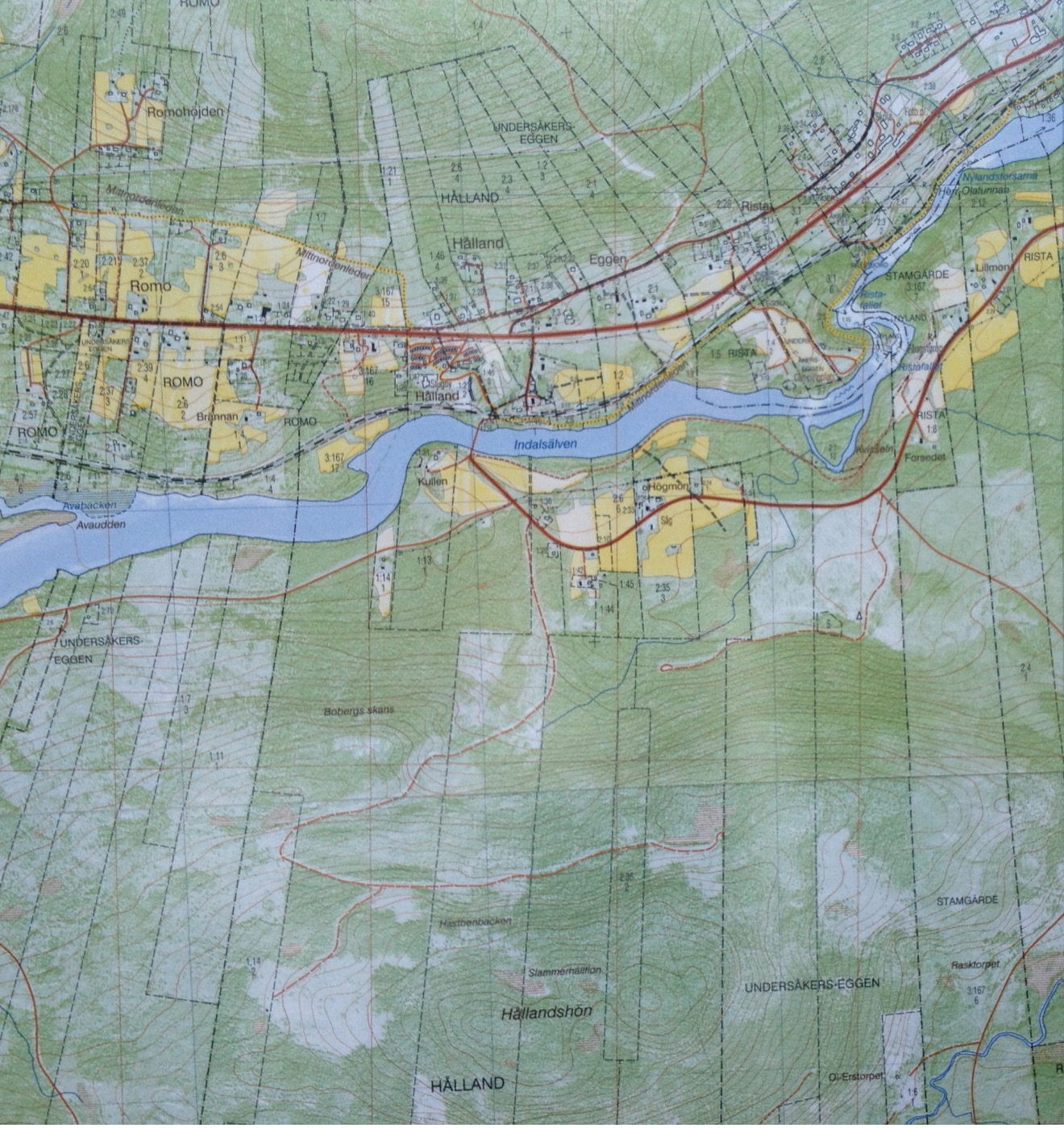

In the lower right of this map you can see the “Ristafallet”, a well-known waterfall in the area. Annette and I decided to drive there the next day, see the falls, and stop by the farm listed as EGGEN by Google maps. My goal was still to get a picture next to a road sign, but now we had a chance of meeting someone who might know more details about the area.

My Homeland Eggen

We drove out to Eggen the next afternoon, after visiting the cool “Jamptli” historical park in the morning. It was easy to find Ristafallet, and we took some pictures there.

Afterwards we drove about half a kilometer down the road to Eggen. The area was on a fairly steep hill, and thus there were roads both above and below the farm. We circled the area in the car and we were able to get a good view of the farmhouse from the upper road. We saw that a small group of people (4 adults and half a dozen kids) were hanging out in the front lawn of the farm, seemingly enjoying the sun.

We eventually got up our courage and drove into the farm and approached the people there. I went up to the front gate and all the adults looked over, appearing slightly bemused. A 30-something guy came over, and our conversation went something like this:

Me: Hello. I’m sorry to bother you. Can you tell me where Eggen is?

Him: This is Eggen.

Me: Wow. I’m from America, and I think my family may have come from this area. Have you heard of Petter Åberg?

Him: I don’t recognize that name.

Me: Ok… I have this little passage from a book here [handing him a copy of the “Born in the snow” story]. This story mentions a couple places in Eggen. Do you think you could help me find them?

Him: [reads the story]… Oh! I know this story! My mother told me this story all the time! Many people know this story. Are you related to this guy?

Me: Yes, I’m pretty sure that’s my great-grandfather.

Him: My mother knows all about this stuff, and she’s on her way here now. Why don’t you join us and we can talk to her when she gets here.

So with that, we sat down outside with Olle Dumky (the guy I initially talked to… last name pronounced DUM-koo), his wife Rebecca, their three kids, and their friends Robert and Madeline Humeur, who were visiting with their kids from southern Sweden. Olle gave us a picture of his younger self that he was very proud of:

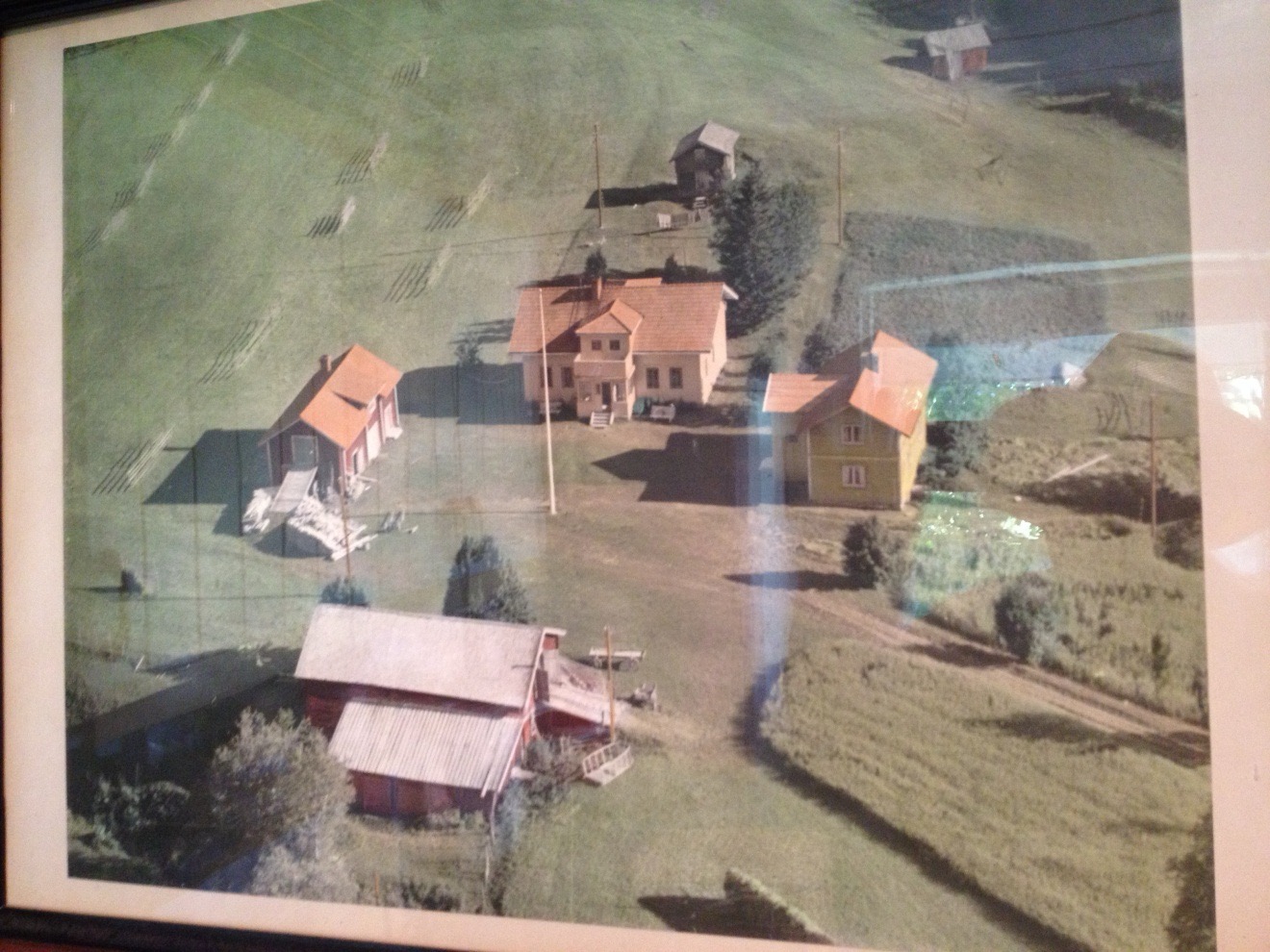

He also showed us around his home (showing off his geothermal system), and I took this picture of a photo of their farm that he had on the wall.

It was a beautiful sunny afternoon on the farm, and we had drinks and talked a bit about my family research and how the various properties in Undersåker were named. They had a cool Swedish map that they showed us:

You can see that Undersåkers-Eggen is listed both in the bottom right, and the upper center. That seemed weird to me. The Swedes explained that the properties were long and thin, so that each landholder could have access to the different types of terrain in the area. At the center of the upper edge of the map is the top of a small mountain. The land is steep from there to the river, and south of the river is much flatter foothills. The properties stretch down from the top of the mountain, across the river, and into the foothills, so each farmer has access to land for farming, hunting and fishing. I found it interesting that these property lines are now visible from Google’s satellite view. You can see how various owners used their land differently:

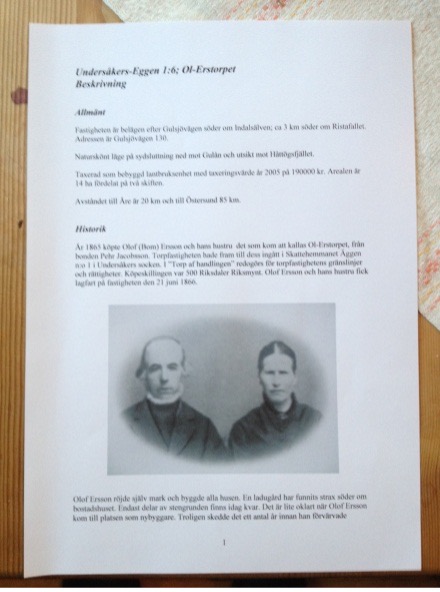

Ol-Erstorpet

Olle’s mother Gunvor soon arrived. She didn’t speak much English, but she recognized the passage from “My Homeland Undersåker” immediately. She went into her house (right next to Olle’s), and came back with her own copy of the book. They talked (in Swedish) about the locations mentioned in the story for a bit. Then they announced that were pretty sure that they owned the cottage in the story. They invited us to stay for dinner, and then they would drive us down to the cottage afterword. (Daylight lasted until about 10pm that day). Here’s a shot of Olle and Gunvor and me.

You’ll notice that I’m wearing a neon yellow Swedish hardware store hat. Over dinner, Olle’s dad said he liked my hat (see the waterfall pic above). I offered to trade hats and he readily agreed. So I now own a hat with genuine Eggen dirt ground into its brim.

After dinner, some of us piled into one of Olle’s trucks and drove down to the family’s cottage. Halfway there, amongst some fields and woods, Gunvor ordered that we stop the car and all get out. She led us through a couple fields and then pointed at a tree, indicating the exact location where Petter Åberg was born in the snow.

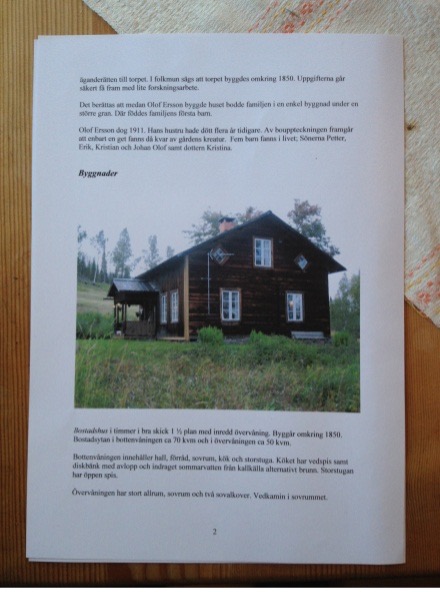

We continued on to the cottage, where a couple of Olle’s friends were staying. It was pretty solid for a structure over 100 years old.

You can see in the last picture that Gunvor is looking through a three ring binder. It turns out that the cottage has its own little history book, including all the previous owners and details on the original builder.

I haven’t had this history translated yet, but the gist of it is that Olof Ersson built the cottage starting in 1850. This is the same Olof Ersson who is the father of Petter Olofsson Åberg. This cottage was built by my great-great-grandfather.

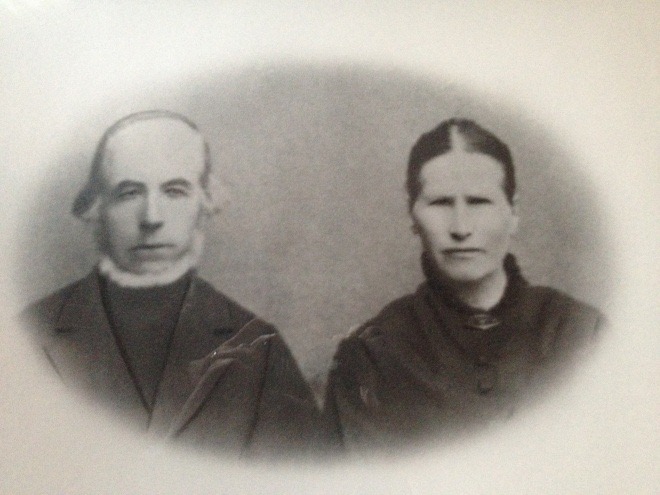

Notice the picture of Olof and Kerstin on the first page of that history. It’s actually a copy of a larger picture hanging in the house. You can see it on the wall to the left here.

As we were about to leave, Gunvor told me that she wanted me to take the picture as a gift. I gave her a huge hug and said no no no. I wanted the picture to remain with the house. In honor of old Olof, who build the thing, and in honor of pool Kerstin, who gave birth to my great grandfather, all alone in the snow.

On our way, out, we saw the sign for the cottage.

It says “Ol-Erstorpet” which means “Olof Ersson’s Croft”. A Croft being a small plot of land for farming.

Epilogue

We have contact info for the Dumky family, and we’ve asked them to visit us in Seattle when they can. We’re sending them a gift package with some jewelry for Rebecca and some fishing lures for Olle. We hope we see them again.